Chicago was a damp. The city had been drowned the two days prior; fat, sticky rain sheeting the Loop and erasing the banks between the river and the streets. I was hiding out in the Siskel theater downtown. I wasn’t watching TV. Safe from the rain and thinking of little but the feature I’d come for. I should’ve never turned on my cell phone.

I grew up in South Florida. I have a friend from Cleveland. She texted a half dozen times during my movie. Many exclamation points. Very athletic profanity. I had not spoken to her in a month at least, yet had somehow managed to earn her rage. It took five minutes to learn the context: LeBron James had gone on national TV to explain after a painfully staged delay that he would leave her Cleveland Cavaliers to play for my hometown Miami Heat.

She was not particularly happy with me. I told her I didn’t cause the damn ESPN special.

“I know. I’m just pissed. It’s not your fault.”

I knew it. It was Michael Jordan’s fault.

_ _ _

This is not a story about LeBron James; not entirely. In the interest of disclosure, I happen to be a rabid fan of the Miami Heat, but that devotion was fomented during the days of Eddie Jones and Brian Grant and Anthony Mason and Alonzo Mourning – a potentially bruising lineup undone by Zo’s kidney. My favorite teams started Lamar Odom at forward and some kid a season out of Marquette at the two, and they never contended for anything. Besides, far too many people have written far too many words about LeBron directly. That’s not important.

What is important is the fact that those words were written, and that more follow daily. I type this as the Heat prepare for an NBA Finals appearance against the ostensibly morally superior Oklahoma City Thunder. The sheer tonnage of verbiage employed in analysis of James’ play is astounding. We read endlessly and write fervently about LeBron and LeBron and more LeBron. Sometimes it is written that we pay too much attention to LeBron, which is a wonderful kind of looping paradox the chicken and its egg could never themselves sort through. He’s endless and everywhere; the one man whose media presence seems capable of combatting the thrall of the NFL on Sportscenter. Really, those seem the only two sports stories of the entire summer thus far: American football exists (praise Jesus and Vince Lombardi), and LeBron James is but isn’t but maybe is after all a choke artist.

The reason that LeBron James is maybe a choke artist is because he is supposed to elevate his considerable talents to some previously unattainable level of athletic achievement when the game is almost over (not unlike what is expected of Spider-Man in a scripted movie, really, but I digress). When James fails to do so – when he doesn’t become abruptly better than he already was, and in achieving this angelic state destroy the opposition by not missing basketball shots anymore – a bizarre wave of anger, bile, cheers, and some sort of vicarious regret sweeps basketball fandom generally. It was formerly acceptable for him to fail attempting such exploits, so long as the exploits were consistently attempted (victories were occasional byproducts). When he joined former rivals on an ostensibly better team – and did so via gaudy press tour – his prior failures engendered rage. He had decided not to attempt messianic basketball while expecting championships, and thus he became a coward.

What this means, naturally, is that whatever James is, it is not enough. His competitive exploits are not interesting in and of themselves; they’re part of a list: some items checked; some unchecked. Whether or not he performs well, or that performance thrills a paying audience – theoretically the twinned goals of any professional athlete – a large portion of the sporting public views him dimly. Because no matter what he does, he is not doing what he is supposed to do according to previously determined criteria. James cannot be accepted, essentially, until he becomes what some guy sipping Budweiser at an Akron bar expected James to be when James was drafted. According to us as fans, James is not quite like we wanted him to be in high school, and we demand penance from him (or drawn by other teams defeating his) until he meets our aspirations on his behalf.

What LeBron James was supposed to be is Michael Jordan.

_ _ _

Jordan is excellence deified in the world I grew up in, or at least the suburban American edge of it. I remember well the front-page, banner headline of his retirement – and my paper covered the greater Fort Lauderdale and West Palm Beach area; not exactly Chicagoland. There was genuine sorrow that this legend of his own time would deprive us of such scintillating prowess. He is, to the imagination, so fundamentally perfect at his chosen discipline that the best and laziest way to describe dominance is to say, simply, that a person is the Michael Jordan of their field. The person who wills their goals to existence by their own transcendence.

What is strange and in fact discomfiting about this is the fact that Michael Jordan is not, in this sense, the Michael Jordan of basketball. He is the Wayne Gretzky of basketball, except that he was never that good at basketball.

Michael Jordan did not score the most points. He did not record the most assists. Gretzky did both. Gretzky owns, in fact, just about every essential record in hockey, despite the condensed league that existed before his time or the advances in training and technique afterwards. Gretzky put such an enormous numerical gulf between himself and the others in his profession that he seems, statistically at least, to have been about twice as good as the nearest competition. He scored over 200 points in a season multiple times. No one else did it once, Lemieux’s valiant effort notwithstanding. Gretzky won titles like Jordan, became a franchise face like Jordan, made lesser teams better like Jordan, but also thoroughly obliterated almost every statistical hockey feat available at a rate far higher than anyone else around him or after him. The idea we have of Jordan – that he not only won, but was impossibly better than everyone else in the league before or after – wasn’t necessarily real. It seems to have been true of Gretzky. But we don’t care about Gretzky like we care about Jordan. I mean, for God’s sake: Gretzky played hockey.

While Jordan was a superb athlete and, quite possibly, the best at his work, our perception of his crushing superiority isn’t actual; not to the level we like to assume. What we believe about Michael Jordan is not the entire truth about Michael Jordan, despite his immense skill. We seem to have held the idea first, and pinned Jordan’s face to it. Jordan embodied what we already wanted to see.

What we wanted to see – and what we still believe in – is someone who, through a stubborn (and quintessentially American) work ethic, tireless devotion, and initially misunderstood talent, subdued the world to their will. Michael Jordan, in this prism, won basketball games because he damn well wanted to, and that was the end of it. In our minds, Michael Jordan is the guy who gets what he wants, takes no prisoners getting it, and leaves no apology. He doesn’t owe an apology. Because he worked harder and was intrinsically better, Jordan doesn’t need to explain himself to us. And we love him – or this imagined version of him – for these very attributes. Unless you happen to be Canadian, Wayne Gretzky was just a good hockey player.

_ _ _

Johann Sebastian Bach is a profoundly famous musician. He’s quite possibly the greatest Western composer who ever lived, though of course those fellows working Vienna in the 1790s get an equal amount of acclaim. The point is, Bach might be well considered the Michael Jordan, in our asinine parlance, of music. Or at least its Magic Johnson (there’s a horrifying buddy comedy lurking somewhere in that paragraph).

The problem with that perception is that J.S. Bach died without fanfare and his music was not rigorously collected and stored when he passed. His genius was not really, by our standards, packaged correctly. He was a church musician – equivalent, really, to a local functionary or tradesman. The idea that anyone would know about his work after his own lifetime – let alone multiple lifetimes later – would have been unequivocally bizarre to him. When he died, he was considered a bit out of touch, stylistically, with the times. The world moved on; the choirmaster of Leipzig was left to small note. His work was only recovered when a later composer found it used as packaging at a butcher’s shop.

This seems – not to put too fine a point on it – bad. Dismal, somehow. Bach, we figure, was perhaps depressed by this turn of events. And in truth, maybe he was disappointed. But there’s no historical record to indicate excessive bitterness. This was the way of things: artists worked to provide set services. When they died, new artists performed the same services. If Bach was saddened by a life without fame as some sort of Baroque rock star, it might have been a bit odd. He actually seems to have been happy, or at least cantankerously diligent about his work.

The reason, then, that some of us might assume disappointment of Bach is that we often draw lines between professional success and happiness, or extreme professional skill and fame. This is not news, but it’s neither is it untrue: if you are frankly outstanding at something, to die with it bypassing you is in our world a great catastrophe. Being good at something for the sake of it isn’t necessarily our goal. We seem to assume that the reason to be good at something is so that people can cheer you on while you do it, thus allowing you to wear the better clothes on the way to the better car in demonstration of your better self.

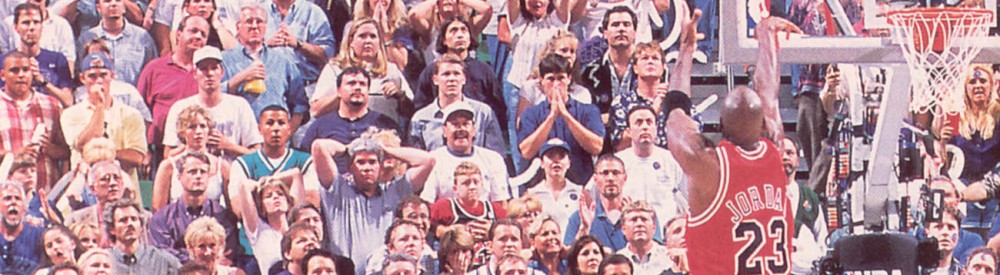

Bach wouldn’t really be able to work today the way he did. He’d need an agent and a card and someone would always be telling him to sell himself. He’d need to strut in front of thousands of people in each city he visited. Tediously rewriting chorales for Sunday performance doesn’t square with our brand of greatness. Our brand of greatness dunks from the foul line on national TV and gambles its excess wealth on the weekend.

_ _ _

Phil Jackson is telling me about MJ. How he – Jackson – became a believer. “You win,” Jackson glowers, “from within.” Then the Gatorade logo screams at me, intercut with footage of Jordan’s legendary Flu Game, in which Jordan was very sick but still very awesome because he wanted it more or something. Or, as the commercial explains via Jackson, because Jordan won from within.

What’s always amusing about this ad is that the central conceit of the piece – Jordan willing victory from places in his competitive soul that transcend physical limitations – is stated in service of a contradictory message: buy the drink Jordan drank, and you too for the low price of whatever can physically possess his intangible qualities. Jordan’s sporting deity is being sold in orange liquid extract. The legend fuels the product fuels the legend (the last by way of a dedicated marketing arm).

Gatorade and Nike became Gatorade and Nike largely by the power of Jordan’s dunks and the odd last-second jumper. But Jordan also became Jordan because of Gatorade and Nike. Fifteen years later, I see footage of the flu game because fifteen years later MJ still sells Gatorade. I don’t see footage of his missed shots, or his early playoff exit after Retirement I. I don’t hear about the Wizards. I don’t hear about Kwame Brown. Jordan’s professional missteps – to say nothing of his personal failings – are not allowed in the public consciousness. The shoes he wears make him who he is, because he was good enough to wear the shoes.

The cycle is dizzying, and as near as I can figure the tacitly preached lesson is this: If you are a superior person, you will have the goods of a superior person. If you are not a superior person, you need to purchase the goods of a superior person. Regardless, you need to buy things. Greatness is indefinable, hard-won, and inborn. But it’s also something you can attain for cost plus tax. You win from within.

Of course, the other thorny philosophical question of the spot is this: can Phil Jackson be the Michael Jordan of coaches when he coached the Michael Jordan of basketball players?

_ _ _

No one wants to be Eli Manning. Perhaps there’s a kid out there somewhere in the suburbs of NYC whose father wears a number ten jersey at all times and who tries as a result to throw like Eli in the backyard. But really, even that kid will eventually attend high school, where he will realize that socially Eli is not the most desirable athletic idol, and adjust to Robert Griffin III, or maybe another Giants player if NFC East cross-fandom is frowned upon. You want to be like Mike. No one wants to be Eli Manning.

This is probably because Eli Manning – for reasons other than being named Eli – is very distinctly and obviously uncool. He looks like the love child of Ron Howard and Bruce McGill (that is, he has Opie’s innocent demeanor and McGill’s jowls). He talks like he’s not quite certain how he got in the room, and appears only dimly aware of his surroundings at any time, which makes observation of his pocket alertness a strangely dissonant experience. Every time the camera catches him after a play, he appears alarmed that it actually happened, regardless of whether or not he did his part. I’ve seen Eli make superhuman throws that would have Brady or Other Manning glowering in confidence for a week, only Eli’s face crunches painfully and he appears apologetic for his own brilliance. This is not really cool. It’s cool to stare grimly into the distance, waiting for Sergio Leone to zoom in on your face (I hear castanets and a solo trumpet every time Peyton throws a touchdown).

And the thing is, Eli does have it: brilliance. It’s simplistic and naïve to solely equate the performance of a starting quarterback with football victory, but it bears note that Eli has defeated Brady twice in the Super Bowl and played with command in both wins. Eli’s seeming immunity to pressure is stunning. Much is made – which is to say too much is made – of what is deemed clutch performance, but whatever it is and however described or quantified Eli has enough clutch to spare. He performs well generally, and then when circumstances appear most dire and millions of people await his next pass he simply continues to perform well, as if a first down in the first quarter were an equivalent goal to a touchdown in the fourth.

Eli sells things. He’s a championship-winning quarterback in New York City; advertisers love him as an idea. But he doesn’t sell things the way Jordan does. Eli appears in a commercial looking, as usual, a little stoned and quietly terrified of the modern world (really; I feel I need to pat his shoulder and explain motor vehicles to him). Eli himself is not telling you what to buy; he’s appearing for a fee in someone else’s pitch. That’s all.

Jordan communicates disdain. It’s maybe – maybe – not even his fault; that’s just how he’s sold; the quality in marketing that makes him desirable: Jordan is cooler than you are, thus better than you are. He sells underwear – underwear, for God’s sake – by wordlessly unmanning a procession of poorly-dressed schlubs who have the audacity to share his oxygen. In half these spots he doesn’t even say three syllables; just shakes his head and wears the hell out of his Hanes. Michael Jordan tells you that he uses a product, and that he doesn’t give a damn about you as a human, then walks off. So naturally we want what he has, because it would be nice to truly not give a damn what others think. It would be nice, at least, to have the approval of someone who doesn’t need our approval.

So ultimately, despite having the Gatoradian attributes we prize in our athletes, Eli isn’t cool because he doesn’t look cool. He doesn’t smirk. He may even, God help him, be earnest or worse: sincere. And there’s nothing less cool than meaning what you say and expecting people to take you seriously. I have no idea if Eli is straightforward or sincere; the point is that he looks like it, and that’s enough. Eli Manning has two rings, the run of New York City, and, to put it indelicately, stones of granite. But he doesn’t look the part, so he isn’t awarded the part in the popular consciousness.

Michael Jordan looks aloof, keeps distant, talks down, and probably smirks when he dreams. Somehow, that looks cool. Somehow that’s more desirable.

_ _ _

Michael Jordan once scored 63 points in a playoff game. His team lost. I didn’t know that last part for years; all I knew – all that I was told by talking heads and retrospective highlights – was that Jordan once scored 63 points in a playoff game.

There’s a commercial running alongside Phil Jackson’s Gatorade bit these days. A montage of past NBA champions. The gist is that individual records will fall, but championships will last forever. Bird, I think, is giving the voiceover. It’s very dramatic. But I don’t think it’s true. As a younger fan leaning on what ESPN tells me and Wikipedia knows about the NBA for league history, I can’t tell you exactly what the year was, who won the series, or who took the title that year. But I can tell you that Michael Jordan once scored 63 points in a playoff game.

_ _ _

Tim Duncan doesn’t look like he cares. This ought to bode well for his chances of cultural glory – Tim Duncan might be cool. 21 for the San Antonio Spurs is a legendary basketball player himself. He has rings to spare. A long career. He stares down the opposition with indifference I personally wish I could at least approximate.

But he has a different limitation on his potential cultural glory: Tim Duncan doesn’t merely look like he doesn’t care what you think. Tim Duncan actually doesn’t care what you think. He rarely if ever tells you what to buy on TV, unless you happen to live in the greater San Antonio area. He doesn’t talk of his own greatness, because he rarely talks at all publicly. He doesn’t want to be famous. He has the toys and the power to be a legend – maybe not like Jordan himself, but certainly somewhere above Eli. Yet Duncan shrugs it all away. Duncan really doesn’t give a damn: he just wants to play basketball and go home to his family. And he wants to do it outside of the big city. You get the impression from his sparse interviews that he worries San Antonio is itself too big.

Eli isn’t cool despite being clutch and rich and famous. Duncan isn’t cool because he is content. Content is boring. I wonder sometimes how that happened.

_ _ _

Ultimately, the concern – the fear – is not merely that we look past people like Tim Duncan for their lack of show. It is that we do not fundamentally value them. People like that exist at a high level of excellence for a number of years, then retire or fade away through changing cultural desires and that’s it. Theoretically, our society values competitive achievement above almost anything else. Gatorade and Nike preach this daily. The ethos permeates academia. Many of our richest and, almost by extension, most powerful citizens are characterized as risk-takers of high professional achievement. Yet we do not value Tim Duncan like we value Michael Jordan.

They are both good at the same thing. They have enjoyed very comparable success. Yet Tim Duncan has a rather modest life – and lives off modest means, relative to his incredible earning potential – and a family he loves. He has remained married to one woman for a decade of his playing career, and has lived in one small city for longer. When his playing career is over, we might not see him much at all. Tim Duncan is happy, as near as those of us who don’t know him personally can tell. He will probably just be happy forever, long after we’ve forgotten about him.

Michael Jordan sits courtside at Charlotte Bobcats games, looking out at the arena he used to own, and fading further and further from the glory he knew. He is a living, breathing demigod in 21st century America, with enough money to live whatever way he pleases, and he pleases to sit courtside at Charlotte Bobcats games because it’s the closest he can get to what he once held. I feel that if a man watches Bobcats games repeatedly, he is probably not very happy. That’s a quip, of course, but it’s also true: our hero – the man LeBron James has sinned by not becoming – is quite possibly not very happy. He was good at something, but he was also ruthless and compulsive, and ultimately bitter about everything if his Hall of Fame induction speech is believed. He won until he could not win anymore, and it doesn’t seem to have been enough to make him feel substantially better than the rest of us. Yet his name is our cultural shorthand for success.

Michael Jordan ruined everything. It’s not really his fault; he’s just the face of the belief we enjoy: The belief that you ought to be better to get more, and that he who has the most wins. That digging deep into some psychic reservoir and willing victory is a virtue far outstripping patience, prudence, and analysis generally. That proving others wrong about your skills – and by extension, your worth as a person – is a healthy motivation for an entire life. That maximum performance in small, pressured windows of time is far a far superior measure of a man to regular performance sustained diligently over large stretches of time. That glory is achievement and achievement should result in glory; glory the end of all things. Be agressive; be single-minded; be superior; be ruthless in pursuit of your own excellence; bathe in adulation. That’s the credo we attach to Jordan.

I don’t know him personally and never will. And I’m sure he never thought his last name would be cultural shorthand for anything. But the idea of the man – our idea, really, of what constitutes ultimate success – makes for a grim statue, and that statue leers over the way we sell to each other, the way we view success, and the model of work we aspire to. Michael Jordan ruined everything.