As I have mentioned previously in the brief existence of this space, I am a fan of the Miami Heat. A raving, potentially mentally unseated fan. This is the kind of thing that happens when, growing up in Delray Beach, Florida, you begin around the age of eleven to obsessively break down the box score of every game in the NBA before school, and to especially watch all 82 games, if humanly possible, of the Miami Heat’s seasonal campaign. You begin to hate New York City, even though you’ve never been there, and jump manically over the couch when the TV tells you that the number ten pick in the draft is going to be Caron Butler, because Caron Butler was a monster at UConn (and became a near star, by the way, before the derailment of injury). A bit later, when some guard you just saw rock the Final Four – for Marquette, which you dimly assume to be somewhere probably north of Florida – is announced as the number five pick, you nearly pass out. Clearly – clearly! – this Wade kid is going to be the best player in the draft, notwithstanding that LeBron noise. (You also, like your father, refer to him as a “kid” even though he’s something like six years older than you.) Brian Grant – a player forgotten by sportsdom generally – becomes a lifelong hero. You develop a horrifying desire to actually hug Stan Van Gundy. Alonzo Mourning is like Obi-Wan and Han Solo at the same time. Pat Riley is something between the Godfather and, well, himself, which is just about as cool.

So when, sometime after all of this, the Heat win their second NBA championship on the rocky shoulders of LeBron James, it is more than a little exciting. Simultaneously in spite of and because of the rage leveled against him, you adopt him as a sporting hero on the level of Dwyane Wade – a category of personal esteem generally unattainable by humans. You jump and scream and dance moronically when the final buzzer barks, ending up half-naked in the street shouting joyful obscenities at no one in particular. It feels as if you, personally, have won the NBA title.

When the thrill subsides slightly, it occurs to you that this behavior is perhaps intrinsically unhealthy, and by necessity somewhat ludicrous. So naturally you want to write about it.

_ _ _

At some point, we all watch sports to root. Many of us watch sports exclusively to root. Some are, by profession or disposition, more aloof and simply analyze; running the play through our minds as it happens. I don’t think either of these approaches has something on the other, necessarily. I enjoy mapping stratagems, or attempting to, more than many fans, and I think sport generally could use a good bit more thought by its audience. But no matter how coldly you calculate the game internally, at some point you will root. More often than not, we seem to watch in the first place because of rooting interest.

This is absurd, really. I feel almost physically ill when confronted with a Heat playoff loss, but their failure or success has nothing to do with my work or aspirations. I simply like a game I’ve never really been able to play myself, grew up in South Florida, and found at ten years old flaming basketballs to be incalculably awesome. But none of those things change the bizarre genesis of rooting interest; of having a side in the fight of professional athletes. Without it there’d be no reason to have sports. But rooting interest seems like a strange way to have sports in the first place: we essentially ask those wearing our emblem to go and do what we cannot in an artificial and artificially precise environment. Then get upset about their efforts.

I’m certain there is research and academic paper to sort through at this point. I’m sure the Greeks enter the equation, because they’re the Greeks, and any time a question about human nature or cultural history is broached they’re contractually obligated to put in an appearance. But I’m not quite interested in why, physiologically speaking, we feel pain or joy on behalf of athletes. I just want to think about what this sort of vicarious victory, for all its potentially unhealthy ramifications, actually feels like and why.

_ _ _

A friend of mine castigated my fetal-position whimpering during game five of the finals, pointing out that his teams had never won a title and that I shouldn’t be so damn worried about it. He said he wouldn’t even know what that kind of victory feels like.

It feels a little shameful. I’ll put that up at the top. I screamed and cursed and made unflattering comments about much more than James Harden’s beard throughout the playoffs. I acted poorly because of the actions of others, and these others I hadn’t even met. I never will. They’re my team; yes. But they don’t know that. And it wouldn’t make a difference if they did. They’re simply men working in a unique and specialized entertainment industry who happen to, at this point in their careers, wear the emblem of my hometown on their jerseys. So when I throw a tantrum, it’s something past idiotic. And really, even if you root for the Chicago Cubs, tantrums are just unfortunate for grown men. That’s my own fault, of course. But even more relaxed or simply mature fans have the temptation, born of identification, to act out or at least grow dark moods based on the actions of others. That part feels a little shameful.

But this victory, which I had absolutely nothing to do with, also feels personal because of that same identification. And I think the identification is the part that splits real, dedicated fans from those who dislike sports or feel something milder about them: the dedicated think the identification is real.

By real I don’t mean that lack of personal victory in actual life necessitates victory by professional athletes on your behalf. That happens; that’s disturbing and a much heavier topic than what I intend to articulate here. What I mean is that dedicated and invested fans, while (hopefully) acknowledging the lack of personal involvement of the team, do see their emotional link as inherently legitimate. The jersey is just a jersey, but it means a place and an idea and an aesthetic. It does represent a physical reality – an arena and an area and a city or region. The Heat’s flaming basketball is downtown Miami and my adolescence and my undergraduate work and late schoolnights talking sports with my dad. That silly icon links me to all those things that I loved. The identification is real, in that sense.

Further, because of the physical truth represented by goofy imagery, serious devotees of a given team gain a sort of affection for good teams that goes far beyond the winning percentage. Because they live in our worlds – unlike other entertainers like movie stars – we learn the roster. We see these guys striving in isolated, pressured situations to perform abstract ball-related goals, and we learn to love them if they show effort or skill or, hopefully, both. We don’t see how, say, a quality accountant does his work, and it wouldn’t make for a particularly enthralling viewing experience. But we do see players work, and we see how they work, and when, in our cities wearing our emblems, they work well and hard together, it creates an authentic desire to see their efforts rewarded. I was perhaps happiest for Mike Miller and Shane Battier to get rings this postseason. Their health is failing (Miller’s, at least) and their skills are declining, but almost ludicrously, they delivered fantastic performances in the Finals through dedicated effort. This doesn’t mean that the Thunder or Celtics or Spurs didn’t try hard or showcase incredible unity and skill. It does, however, mean that while I admired their work as a lover of the game, I don’t, in a sense, know those players. At least I don’t know them the same way, and all because of the jerseys they wear. Watching Miller badly underperform his designated role for two seasons, then bring it together in the very last game he may play for my old city, was genuinely emotional for me. And I think that’s legitimate.

Sports, further, are lawed environments. Some interpretation of law is needed from officials, of course, but the standards are objective and, in theory, quantifiable. When you step out of bounds, you have objectively put your foot on a clearly marked and measured bit of color visible to yourself, the other players, and a viewing audience. The rules are intended to be objective. It is only the speed of play and some bizarre officiating decisions – like Wade, Durant, Westbrook, and LeBron all being allowed about sixteen steps on the way to the basket – that prevent games from being truly objective. The rules are granite; only interpretation of those rules can be incorrect.

All that to say: when I achieve victory in my life, it is always – or nearly so – an achievement noticeable only to me that doesn’t immediately change my daily life or state of being, and results in no reward. We do well in work or life and the moment, uncatalogued by others, leaves us generally not so different than we were previously. Sports allow us, vicariously, the thrill of a victory quantified, recorded, and undisputed. When you win the game, you have definitely won the game. Would that life were always so.

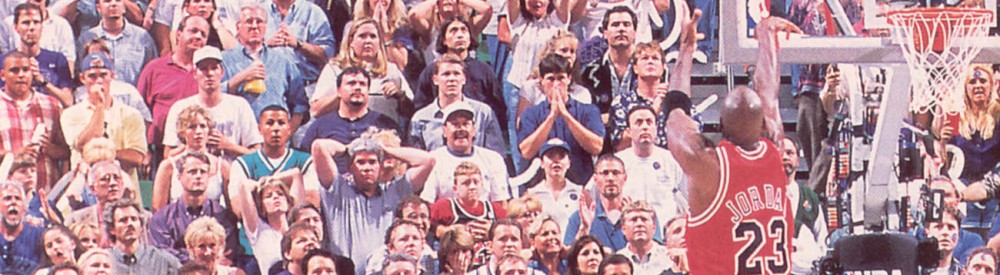

Finally, the type of work done here is entertainment, ultimately. I didn’t watch James, Wade, and Bosh get rings for a good sales quarter. I watched them fly around an enclosed space to generate points for placement of a ball. It was, like all excellent sport, fast, physical, dynamic, and visceral. The game itself is visually exciting, when played at a high level, because we are – not to wander too far abstract – physical beings watching men push the human body to its highest levels of agility, strength, balance, and vision. I think many of us drift in affinity towards one sport or another for the specific skills required and the way it looks attempting those skills. What we value and find physically exciting in our world is, to an extent, modeled by athletes. It’s just fundamentally cool to watch Messi rocket a shot to the top corner, or Calvin Johnson to leap through the mesosphere to snag a football, or Malkin flick a wrister under the goalie’s glove. Or LeBron James dunk with primal ferocity.

So when the Heat took a championship in a wildly exciting sport by joining professionals together under an intellectually interesting strategy, in a field where competition is both aesthetically pleasing and more direct than in most of life, and did so wearing the emblem of my city with players whose personalities and tendencies became well-known to me, it was an intellectually and emotionally rewarding experience, even though I had nothing at all to do with it. And I feel no apology is owed for that. Provided its proper place is awarded – i.e., a place beneath personally victory or greater philosophical tenets than victory in the short term – there’s nothing wrong with vicarious winning. It’s actually pretty spectacular. I hope every sports fan gets that reward for their loyalty.

(Unless you pull for the Celtics, of course.)